SADC, a club for presidents, source of regional instability

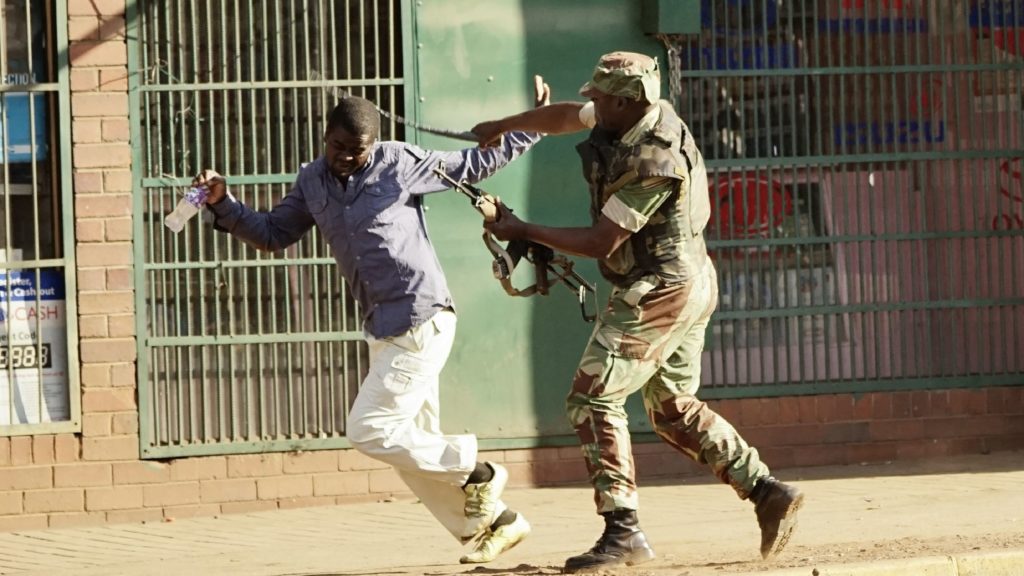

Zimbabwe soldiers beating up civilians in Harare

By Arnold Tsunga & Tatenda Mazurira

Southern African Development Community (SADC) Summits never fail to come up with the most colourful and promising of themes. The 40th (SADC) Summit currently underway is themed: SADC: 40 Years Building Peace and Security, and Promoting Development and Resilience in the face of Global Challenges.

In light of the Covid-19 global pandemic, the annual Summit is for the first time in history being held in a virtual format. Mozambique is coordinating the summit from 10-17 August 2020. Despite the colourful and hopeful theme the summit is being held in the midst of serious human rights violations with total impunity in Zimbabwe, where the government has mastered the art of using Covid-19 measures to stifle democratic participation and demands for accountable governance.

As Maputo is co-ordinating the summit on peace and security, the main news was that Mozambique’s army had lost the key port of Mocimboa da Praia, to Islamist militants on Wednesday 12 August 2020. The Islamist militants now control the territory and have a resources foothold in southern Africa, given that Mocimboa da Praia is near the site of natural gas projects worth $60bn (£46bn).

This could spell serious calamity. Southern Africa might as well kiss goodbye the long-held notion of southern Africa being seen as the most peaceful and stable sub-region in Africa.

This week’s roundup looks at the SADC Summit and issues around it.

Virtual Heads of State summitThe virtual summit is taking place with a reduced agenda to allow the leaders to focus more on critical issues in the region, including: co-ordinated response to Covid-19; review progress towards the development of a post-2020 SADC agenda; measures to address food insecurity; receive a progress report on the implementation of the industrialisation strategy; take stock of interventions undertaken to promote peace and stability member states; and renewal of institutional leadership.

Over the years, SADC has been widely criticised for failing to tackle regional peace and security challenges, with some critics labelling it a ‘toothless bulldog’. The inability to resolve conflict is best demonstrated by the ignominious collective decision of the SADC heads of state and government to disband the sub-regional judicial organ, the SADC Tribunal, merely because Zimbabwe disagreed with a binding judgment of that court.

Although some argue that in the absence of SADC, violent conflicts could have been more pervasive in southern Africa, the body’s interventions have not effectively dealt with violent and political crises, thereby undermining development. This is supported by the notion that it is inconceivable to have socio-economic development in the absence of peace and stability.

Toothless bulldog?

SADC’s inherent weaknesses are both historic and institutional.

First, the co-operation is rooted in historical ties steeped in anti-colonial struggles such that liberation war parties view themselves as each brother’s keeper.

Second, the recurrent electoral crises produce contested outcomes and arguably illegitimate leaders. This unfortunately creates leaders who are not fully accepted by their populations and therefore rule by coercion and not consent. This results in unaccountable governance that breeds corruption and conflict. If unaccountable leaders of questionable legitimacy are at the helm of SADC, what reasonable expectation is there that they will fight impunity and work towards justice, peace and stability?

As political instability in many SADC states is driven by complaints of inability to conduct free, fair and credible elections, one thing SADC should focus on is to invest in strengthening the independence of election management bodies. Only South Africa, Namibia, Botswana and lately Malawi seem to get it right. The SADC Summit should devote attention to this to create a basis for sustainable peace and stability. It is unlikely that it will, though.

This year’s theme recognises that peace and stability are key preconditions for sustainable development and regional integration. However, SADC is also notoriously inefficient or incapable of enforcing its own protocols. The weak, and at times nonexistent, enforcement mechanisms for its decisions make the SADC a toothless bulldog.

Brotherhood philosophy

The Organ for Politics, Defence and Security (Organ) launched in June 1996 is the formal institution of SADC with the mandate to support the achievement and maintenance of security and the rule of law. Its leadership is in the form of a ‘troika’ system comprising a current chair as well as the previous and incoming chairs.

Zimbabwe currently chairs this Organ, which is charged with ensuring peace and the rule of law in the region.

However, when it comes to the crucial responsibility of building peace and security, efforts have been undermined by the ‘brotherhood’ approach that has resulted in the regional bloc failing to collectively solve the socio-economic and political crises that consequently deepen over time.

Ringisai Chikohomore of the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) characterises this cheap ‘brotherhood’ well. He describes it as member states who “opt for accommodation and fraternal solidarity as an unsaid modus operandi, resulting in a failure to sanction delinquent states.”

The systemic failure by SADC leaders to hold each other to account for human rights violations is seeing southern Africa’s non-violent image fading due to events occurring in various countries in recent years.

Current conflicts and crises in the SADC

Governance issues have ignited the most acute crises in the SADC states for more than a decade. These include coups, disputed elections and political instability, authoritarian rule, civil unrest, abuse of state power and lack of transparency and accountability by governments in their desperate bid to cling to power and authority.

On 13 August prominent civil society leaders from southern Africa met virtually at a regional meeting facilitated by the Southern African Human Rights Defenders Network (SAHRDN) and the Zimbabwe NGO Forum to discuss the Zimbabwe crisis and make recommendations for consideration by the SADC Summit.

The findings were that the government of Zimbabwe is guilty of attacks on democratic space; use of the Covid-19 pandemic as a pretext to clamp down on freedom of expression and freedom of peaceful assembly and association; organised violence and torture and using the criminal justice system as a political weapon.

Their final communique concluded:

Zimbabwe’s human rights problems are highly entangled with the political developments. Similarly, the economy is reactive to political developments. According to the 2019 Labour Force Survey released in March 2020, 74% of Zimbabwe’s labour force is in the informal sector… Zimbabweans are therefore now suffering the triple burden of poverty, unemployment and inequality.

The Zimbabwe government of President ED Mnangagwa, which was born out of the November 2017 coup and a disputed 2018 election, has become notorious at weaponising the law and judicial persecution of human rights activists akin to how the law was instrumentalised during the colonial regime of Ian Smith.

Critics are sceptical that President Mnangagwa as part of the Organ leadership can allow for a SADC-led solution to the Zimbabwe crisis.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa sent his special envoys Mbete and Mufamadi to Harare to try to mediate the low-intensity but high-impact conflict last week, but the envoys returned to Pretoria empty-handed after Mnangagwa apparently blocked them from meeting anyone else from the opposition or civil society.

That the current leaders got away with a soft military coup in 2017, the first time in the history of the SADC that a military coup was staged, might explain why the government of Zimbabwe is able to blatantly violate rights in a serial way with impunity.

Mozambique and Islamic terrorism: Mozambique has a troubled political history. In 2012, Mozambican Renamo rebels took up arms again and, although they apparently lacked the military capacity to rekindle a civil war, they attacked government troops and transport routes, creating economic disruption and insecurity ever since.

In May 2020, there were reports of insurgents carrying out “some of their most daring assaults”, seizing government buildings, blocking roads, and hoisting black and white Islamic State flags in Cabo Delgado’s towns and villages.

Recent reports indicate that the civilian security situation in Cabo Delgado continues to worsen. In Mocimboa da Praia, sporadic attacks by insurgents since July resulted in homes being burned, food supplies looted, and people killed and some kidnapped.

Sadly as the current SADC summit is taking place there are reports that dozens of Mozambican soldiers have been killed, and a patrol boat sunk, while the army says it has killed about 60 militants. The Islamist militants took over and conquered Mocimboa da Praia from the ill-equipped, ill-prepared and demoralised Mozambican army that fled the scene of fighting.

For more than three years now, the SADC region has stared at the prospects of Islamic terrorism getting a foothold in the region via the Cabo Delgado province of Mozambique, where 700 000 people are now affected by the war. Yet such an obvious threat to regional peace and stability has not received any meaningful reaction from the SADC. It will not be a surprise if this summit comes and goes as if nothing is happening.

DRC and potential regression: When President Tshisekedi ascended to the throne in 2019, there was relief that for the first time in more than 60 years there was a transition of power to a civilian leader as a result of elections.

However, political instability and ethnic-based conflict continue. Between October 2019 and February 2020, more than 300 civilians were killed in northwest Beni, North Kivu province, when the Congolese army launched a military operation against a non-state armed actor, the so-called Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), in an attempt to dismantle and expel the group.

There are fears that a power struggle is currently raging between President Tshisekedi and former president Kabila, “who continues to wield enormous power through his parliamentary majority, control of the army and several cabinet ministries, to interfere with the country’s next elections in 2023.”

SADC can ill-afford another full-blooded conflict in the DRC. SADC’s military intervention in the DRC in 1998 has already been widely discussed and criticised as an illustration of SADC’s lack of unity, dearth of co-operation, and ability to be hijacked by national if not private interests.

Zambia and Lungu’s power consolidation: President Lungu came into power after questionable elections. The United States’ 2019 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices in Zambia notes that the country’s last election in 2016 was marred by irregularities.

“Although the results ultimately were deemed a credible reflection of votes cast, media coverage, police actions, and legal restrictions heavily favoured the ruling party and prevented the election from being genuinely fair.

Civil society has of late reported systematic and sustained attacks on the free media in Zambia ahead of the 2021 elections. The following radio stations have been disrupted by Patriotic Front cadres during this Covid-19 period: Feel Free radio station, Power FM, 5FM radio, Muchinga Radio, and Radio Maria.

This systematic and sustained attack on free media in Zambia shows that the militias who religiously carry out these attacks act with the acquiescence of the state. Frankly speaking, no one expects SADC to do anything about this, in the process reinforcing the notion that impunity pays.

Eswatini – Last absolute monarchy in the world: Eswatini remains as the last absolute monarchy in the world, with notable governance deficits. King Mswati holds supreme executive power over the parliament and judiciary by virtue of a 1973 State of Emergency decree.

Why the SADC does not hold King Mswati to account and fully implement the 2005 constitution remains a mystery.

Lesotho and failure to implement the Phumaphi report: Since its return to democracy in 1993, political instability, characterised by excessive meddling in civilian politics by the military, continued to rock Lesotho. In May 2020, former Prime Minister Tom Thabane finally bowed to pressure and resigned. Moeketsi Majoro, who according to analysts faces enormous hurdles ensuring peace and political stability in the country, replaced him.

Such is the political instability in Lesotho that by 2018, when the SADC established a commission of inquiry into killings of the army commander led by Justice Phumaphi, Lesotho had had three elections in five years , after the government collapsed with votes of no confidence in Prime Ministers.

SADC has failed to enforce the full implementation of the Phumaphi report resulting in prime Minister Tom Thabane being ousted and political instability and economic and social suffering of Basotho continuing unabated with the possibility of a fourth election in seven years.

Can Tanzania hold credible elections? Despite the raging on of Covid-19, Tanzanian President Magufuli decided to power on with elections. Tanzanian opposition leader Tundu Lissu, who was shot 16 times in an attempt on his life in 2017, has said he lacks confidence in the electoral commission ahead of his presidential contest in October’s general elections. Lissu accused Tanzania’s electoral officials of serving at the pleasure of the incumbent, arguing that the chairman and the chief executive of the electoral commission were appointed by President Magufuli in an opaque manner, rendering their impartiality questionable.

Lissu has also recently written to President Cyril Ramaphosa in his capacity as Chairperson of the AU, appealing for his own protection ahead of the elections.

Peace, stability and development in southern Africa: A pie in the skyIn 1992, a landmark achievement by the Community was the establishment of the SADC Tribunal. However, it died a slow death as the result of political interference by Zimbabwe after the Tribunal made judgments against Zimbabwe in 2007-8.

It was disbanded in 2011-12.

Hope for the revival of the SADC Tribunal was re-ignited after South African High Court judge Dunstan Mlambo ruled that “if the intention of the Zuma-led government was to withdraw Pretoria from the SADC Treaty and Protocol, consent of Parliament had to be obtained first”. This judgment was confirmed by South Africa’s Constitutional Court in 2018.

If SADC heads of state and government genuinely believe in the rule of law and human rights, then they should prioritise reviving the SADC Tribunal.

It is for reasons such as these that SADC’s institutional framework for regional peace and security is proving ineffective – its leaders are unwilling to enforce democratic principles and to hold each other to account.

While it has established strong protocols on security co-operation and safeguards on democracy and human rights, SADC continues to operate on the pillars of absolute sovereignty and solidarity, leaving a yawning gap between standards and practice.

Thus, according to former Botswana President, Ian Khama

“Most of the time presidents at the SADC and the African Union (AU) hold meetings just to look politically correct … they just go home after that and it is business as usual.”

This reinforces the criticism of SADC as a moribund organisation that is ill-equipped to confront critical challenges necessary for the achievement of real progress.

SADC must be for the people of SADC and not an exclusive inaccessible club for the presidents and heads of state. In its current form and modus operandi, SADC is part of the problem driving instability in the sub-region.

–Daily Maverick

Arnold Tsunga is a human rights lawyer, the director of the Africa Regional Programme of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), and the Technical and Strategy Adviser of the SAHRDN. Tatenda Mazurura is a Woman Human Rights Defender (WHRD) and an election expert.