Mnangagwa outsmarts Chiwenga

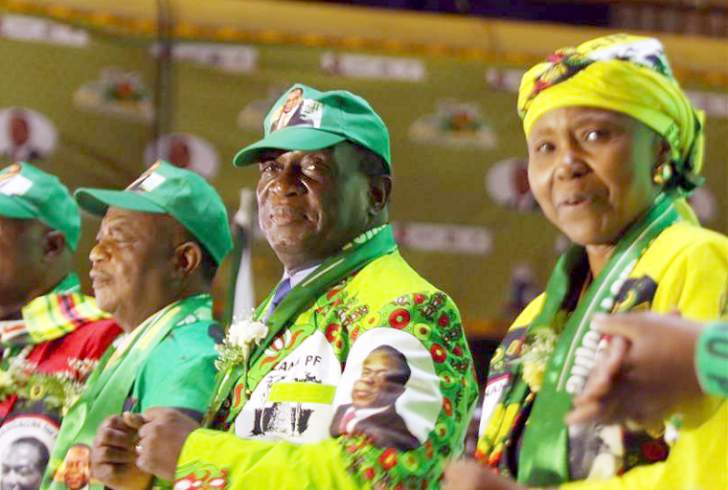

Zanu PF Chairperson Oppah Muchinguri pleads with Munhumutapa spirit to guide President Emmerson Mnangagwa

PRESIDENT Emmerson Mnangagwa is next week expected to emerge triumphant at the crucial Zanu-PF elective congress after a fierce power struggle – characterised by scheming, backstabbing, a grenade attack, poisoning and purges, as well as fears of yet another military coup – over the unresolved party leadership rivalry between him and his deputy Constantino Chiwenga.

This followed the removal of the late former president Robert Mugabe through a militaty coup in 2017.

The Zanu-PF congress will be held from 26-29 October at Robert Mugabe Square – also known to the opposition as Freedom Square – in Harare. It is the first full congress since Mugabe’s dramatic ouster and subsequent death.

Mnangagwa and Chiwenga are still fighting over the spoils of the November 2017 coup.

Chiwenga, who engineered Mugabe’s toppling and put Mnangagwa in power, thought the President would serve only one term and hand over the reins of power to him in 2023, but that has been publicly rejected, fuelling tensions and hostilities.

A senior Zanu-PF leader told The NewsHawks: “It’s now fait accompli. Mnangagwa will emerge as party leader unchallenged. All along it appeared as if there might be a surprise battle at congress triggered by Chiwenga and his faction, but it is now clear that won’t happen. The internal process has taken precedence and ED (Mnangagwa) is the only one nominated for the party leadership.”

The official added: “Chiwenga is weaker at this point in time, especially considering that he was the power broker in 2017. He even had difficulties in getting nominations for the central committee, including in his Mashonaland East home province recently. That is how weak he is now. His name has not even come up during nominations for the top position ahead of congress. He lost it primarily during the provincial elections, where he was blocked, even though his allies had won in some instances. He had done well in the district coordinating committee elections, but now he is contained despite his residual military influence.”

As a result, Mnangagwa will next week conclude the political coup – after the military coup against Mugabe by Chiwenga – he set in motion since the Zanu-PF annual conference at Esigodini, Matabeleland South, from 13-16 December 2018.

Mnangagwa launched a coup against Chiwenga at the conference, which, among other things, resolved that “preparations for the 2023 harmonised elections to begin in earnest” – only six months into his new term of office – in a bid to stop his deputy from taking over from him next year.

After bulldozing the party district coordinating committee, provincial and central committee elections, and securing provincial nominations, Mnangagwa has consolidated power, guaranteeing its retention through congress next week.

Chiwenga has been weakened through the collapse of the coup coalition dominated his allies.

So barring political contingency – the unexpected, the accidental and the unforeseen – Mnangagwa will next week emerge as the Zanu-PF leader.

This will shatter Chiwenga’s plan of being the Zanu-PF candidate in next year’s presidential election and perhaps end up with his idea just being a dream deferred.

Currently Mnangagwa stands alone at the top of Zanu-PF politics.

Sources say Chiwenga has lost significant support in the reconfigured party and the military ahead of congress due to a combination of factors. The army, a source said, is now more worried about the welfare of middle-ranked commanders and the rank and file rather than the Zanu-PF succession issue.

Salaries and working conditions for the military have deteriorated and are now worse than what they were under Mugabe.

“While Chiwenga has residual influence in the army, the problem is that the military is now more worried about its own welfare issues rather than who succeeds who in Zanu-PF because that is no longer a priority for them,” a source said.

“They view Mnangagwa and Chiwenga as the same: they both betrayed them.”

Scared of being ousted by Chiwenga and his faction, Mnangagwa had avoided the scheduled 2019 congress after his controversial ascendancy through a central committee meeting held on 19 November 2017 at party headquarters in Harare.

An extraordinary congress was held in December 2017 to install him as party leader, but the constitutional processes were not followed to the letter and spirit of the law.

Zanu-PF youth member Sybeth Musengezi, publicly viewed as Chiwenga’s proxy, is challenging Mnangagwa’s legitimacy in the courts. He wants the congress stopped until that matter has been resolved as they are intertwined, but Zanu-PF is forging ahead all the same.

Zanu-PF insiders say Chiwenga lost political ground when he fell ill and almost died between 2018 and 2019. From there, they say, he never quite recovered even though his faction has remained intact, with potential to regroup and fight back.

The situation has been worsened by military disgruntlement and a feeling among the rank and file that Chiwenga has abandoned base, and joined political elites for self-preservation and self-aggrandisement.

The fight has been deadly – Mnangagwa has lived to tell the tale after a grenade attack on 23 June 2018 at White City Stadium in Bulawayo, while Chiwenga survived poisoning, according to insiders. The poisoning has left Chiwenga vulnerable to health complications, with some saying it has become his greatest undoing.

Some influential movers and shakers on the power struggle chessboard were purged, while others lost their lives; dying in unclear circumstances under the Covid-19 pandemic cloud; for instance, former military commanders and ministers Perrance Shiri and Sibusiso Moyo, who were critical Chiwenga allies.

After being rescued from the jaws of death by Chinese doctors, Chiwenga now has tight security around him and frequently sees doctors in Avondale and Borrowdale for medical check-ups.

Those close to him say he no longer eats and drink anything at state occasions and Zanu-PF functions for fear of being poisoned.

Mnangagwa, who was weaker compared to Chiwenga when he took over power in 2017, has now ridden out the political storm buffeting his embattled presidency. Among other things, he has the combined effects of Chiwenga’s ill-health and the Covid-19 pandemic to thank for out-muscling his deputy.

Mnangagwa made crucial consolidation moves between 2019 and 2020, while Chiwenga was battling for his life amid poisoning fears.

He was airlifted from South Africa to China in July 2019 before undergoing life-saving yet risky surgery at a military hospital in Beijing to fix his esophagus. He was severely emaciated when he was airlifted. His rivals believed he would not make it, but he made a stunning recovery and returned home in November, amid fears he would take over.

There had been panic in January 2019 that another coup was looming to remove Mnangagwa.

This is confirmed in Mnangagwa’s authorised biography titled A Life of Sacrifice: Emmerson Mnangagwa, which book reviewers and political analysts say exposes the rift between the two.

The 154-paged biography, which Mnangagwa described as a “brief window” into his life, was authored by Eddie Cross, a former opposition MDC high-ranking official and MP.

It depicts Chiwenga in negative light through its narrative.

Cross, Mnangagwa’s biographer and newfound loyalist, said the President will brook no nonsense from those threatening his hold on power, a thinly veiled warning to Chiwenga.

The book reveals that Chiwenga’s appointment as co-deputy, together with Kembo Mohadi (who resigned last year amid a sex scandal), was part of Mnangagwa’s coup-proofing strategy.

Mnangagwa appointed General Philip Valerio Sibanda to succeed Chiwenga as commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces. Sibanda, according to the book, is “possibly the best soldier in southern Africa and a man that was deeply respected in the army”.

“Mnangagwa’s actions drew little attention, but what the President was doing was closing the door on any possibility of the military-assisted transition (military coup) being repeated. He needed to know that the security services were led by men in whom he had confidence as professionals,” the book says.

It says clashes between Mnangagwa and Chiwenga played out when the latter demanded that a state of emergency – Martial Law – be declared during the 2019 riots which had been triggered by a 150% increase in the price of fuel.

“When it became known that a state visit to Russia was planned for the week beginning the 14th January 2019, disturbing intelligence was received that disturbances were planned,” the book reads.

“The President consulted his security chiefs about the threat and gave instructions about what was to happen in his absence . . . The acting President retired General Chiwenga, demanded that a state of emergency be declared and that Martial Law be introduced. This would have effectively meant that the armed forces took over the administration of the state and the commander-in-chief of security services, but General Sibanda refused. He said his orders from the President were very clear.”

This suggests a rift between Chiwenga and Sibanda, the President’s man.

Internet services were suspended during the protests after security forces were deployed to quell the disturbances.

“(After the protests) the country went back to normal as if nothing had happened. What had happened was that the President had stamped his authority on the state. He would not tolerate any challenge even from his closest colleagues,” the book says.

Health problems worsened Chiwenga’s political setback after the abortive martial law attempt. Although Chiwenga has not fully recovered, he is in a better position than he was when he was flown to China as he could not eat or talk. He was being fed through intravenous means and had to undergo an intensive feeding programme before the operation, as he was too weak to be operated on.

Prior to being airlifted to China, Chiwenga had been hospitalised in South Africa and India, giving Mnangagwa an opportunity to consolidate power by, among other tactics, removing his key allies from powerful positions.

The Covid-19 pandemic then dealt him a heavy blow, after taking the lives of his two most powerful allies in government – Agriculture minister Shiri in July 2020 and Foreign Affairs minister Moyo in January 2021 – who, like him, had traded their military fatigues for suits after the coup.

Shiri and Moyo’s death left Chiwenga vulnerable and exposed in government at a time his strongest military backers had been removed from the army, and deployed on diplomatic missions outside the country.

A Zanu-PF official said: “The writing is on the wall for Chiwenga. He will not be able to challenge Mnangagwa. No province has nominated him. His health woes have not helped the situation.”

Chiwenga’s presidential ambitions were confirmed by his ex-wife Mary Mubaiwa, who in court papers filed by her lawyers Mtetwa and Nyambirai Legal Practitioners in January 2020, said the former military commander was fearing that his presidential ambitions were in jeopardy.

Mubaiwa was challenging Chiwenga’s application to dissolve their marriage.

“Defendant avers in reconvention that the demise of the customary law union was brought about by plaintiff’s acute paranoia brought about by his poor health, his being under heavy doses of drugs including unprescribed opiates, his surrounding himself with persons who want to take advantage of him and his belief that his ascendency to the position of presidency might be in jeopardy,” Mubaiwa said.

Mubaiwa’s papers were lodged in court at a time Chiwenga was losing his grip on power after his key military backers, who played a pivotal role in the coup, were kicked out of the army and Zanu-PF, while he was battling a life-threatening illness.

Among those removed were retired Lieutenant-General Anselem Sanyatwe, who commanded troops on the ground during the coup as Presidential Guard commander. Sanyatwe is Chiwenga’s personal friend and confidante.

Sanyatwe was retired alongside several commanders ahead of diplomatic assignments in February 2019. These include the late Zimbabwe National Army chief-of-staff retired Lieutenant-General Douglas Nyikayaramba, who was chief-of-staff responsible for service personnel and logistics, retired Lieutenant-General Martin Chedondo and retired Air Marshal Sheba Shumbayawonda.

In June 2019, Mnangagwa then made another significant move by removing retired Lieutenant-General Engelbert Rugeje from the Zanu-PF commissariat and replacing him with ally Victor Matemadanda, as he seized control of the party, while Chiwenga was incapacitated.

Mnangagwa initially wanted to appoint Matemadanda to the position, but was arm-twisted by the then healthy and powerful Chiwenga, who wanted his loyalist to occupy the position, ensuring he controls the party structures.

Zanu-PF insiders say although Chiwenga tried to mobilise his troops following the massive setbacks, he had ultimately lost ground to mount a challenge.

“No doubt he is in a much weaker position today. After the coup, he was clearly in charge and dictating things. That’s why he was able to ensure that he comes into government with his military colleagues and also ensure that Rugeje is appointed the Zanu-PF political commissar ahead of Matemadanda, whom Mnangagwa wanted,” said a senior Zanu-PF official.

“He arm-twisted Mnangagwa to appoint him vice-president, while ensuring that he remained in charge of defence. Mnangagwa had all but appointed Oppah Muchinguri as his deputy, but Chiwenga would have none of it.

“Everything seemed to be going on well for him until the White City bombing in (June) 2018. We saw his hands getting swollen. His wife’s hands were also getting swollen and, with time, his skin was lightening. We were told it was the effects of the bombing, but we then heard that he was poisoned by his political rivals. Those in his camp say he was poisoned, but I can assure you things would have been different if the general had managed to stay healthy.”

Mnangagwa’s backers say Chiwenga believes his ailing former wife played a role in attempts to kill him, hence his hardened stance towards her. However, no evidence of her direct role has ever been provided.

Mubaiwa’s right arm was amputated in September after she was diagnosed with acute lymphoedema which caused large open wounds on both forearms.

The former model is being charged with attempted murder, among other accusations, and has been frequenting the courts which have refused her request to get her passport to seek alternative medical attention outside the country as she battles the life-threatening ailment, amid allegations Chiwenga may be influencing the decision to retaliate after his poisoning, plot to kill him and Mubaiwa’s perceived great betrayal by working with his enemies in the Mnangagwa camp.